SIGNS AND GESTURES

Gestures such as genuflecting and making the sign of the cross are regarding as non-physical Sacramental.

The Sign of the Holy Cross

On the cross Christ redeemed mankind. By the cross He sanctifies man to the last shred and fiber of his being. We make the sign of the cross before we pray to collect and compose ourselves and to fix our minds and hearts and wills upon God. We make it when we finish praying in order that we may hold fast the gift we have received from God.

In temptations we sign ourselves to be strengthened; in dangers, to be protected. The cross is signed upon us in blessings in order that the fullness of God’s life may flow into the soul and fructify and sanctify us wholly. Think of these things when you make the sign of the cross. It is the holiest of all signs. Make a large cross, from forehead to abdomen, to left shoulder then right shoulder, taking time, thinking what you do. Let it take in your whole being — body, soul, mind, will, thoughts, feelings, your doing and not-doing — and by signing it with the cross strengthen and consecrate the whole in the strength of Christ, in the name of the triune God.

By a Brief of July 28, 1863, Pope Pius IX granted: An indulgence of fifty days, to all the faithful every time that, with contrite hearts, they sign themselves with the form the the Cross, pronouncing at the same time, in honour of the Most Holy Trintiy, the words - In the name of the Father, of the Son, and of the holy Spirit.

Genuflection

Genuflection is a sign of reverence to the Blessed Sacrament. Its purpose is to allow the worshipper to engage his whole person in acknowledging the presence of and to honor Jesus Christ in the Holy Eucharist. It is customary to genuflect whenever one comes into or leaves the presence of the Blessed Sacrament reserved in the Tabernacle. "This venerable practice of genuflecting before the Blessed Sacrament, whether enclosed in the tabernacle or publicly exposed, as a sign of adoration, ...requires that it be performed in a recollected way. In order that the heart may bow before God in profound reverence, the genuflection must be neither hurried nor careless." A common-sense exception applies to a sacristan or custodian for whom it would be impractical to constantly be genuflecting in the course of their duties.

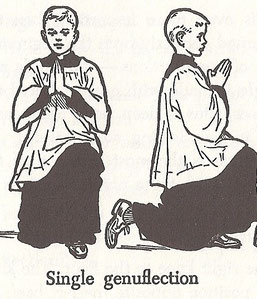

1. Single Genuflection

Only during the later Middle Ages, centuries after it had become customary to genuflect to persons in authority such as bishops, was genuflection to the Blessed Sacrament introduced. The practice gradually spread and became viewed as obligatory only from the end of the fifteenth century, receiving formal recognition in 1502. The raising of the consecrated Host and Chalice after the Consecration in order to show them to the people was for long unaccompanied by obligatory genuflections.

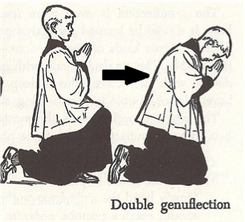

2. Double Genuflection

The requirement that genuflection take place on both knees before the Blessed Sacrament when it is unveiled as at Expositions (but not when it is lying on the corporal during Mass) was altered in 1973 with introduction of the following rule: "Genuflection in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament, whether reserved in the tabernacle or exposed for public adoration, is on one knee."

"Since a genuflection is, per se, an act of adoration, the general liturgical norms no longer make any distinction between the mode of adoring Christ reserved in the tabernacle or exposed upon the altar. The simple single genuflection on one knee may be used in all cases." However, in some countries the episcopal conference has chosen to retain the double genuflection to the Blessed Sacrament, which is performed by kneeling briefly on both knees and reverently bowing the head with hands joined.

Episcopal Practice

Although prayer comes from the heart it is often expressed naturally through the body. Genuflection is an act of personal piety and is not required by the Prayer Book. In some parishes it is a customary gesture of reverence for Christ's real presence in the consecrated Eucharistic elements of bread and wine, particularly in parishes with an Anglo-catholic tradition. Generally, if the Blessed Sacrament is reserved in the church, it is customary to acknowledge the Lord's presence with a brief act of worship on entering or leaving the building. Normally a genuflection in the direction of the place of reservation.

Postures and Gestures of the Congregation at Mass

The Church’s great liturgical tradition teaches us that fruitful participation in the liturgy requires that one be personally conformed to the mystery being celebrated, offering one’s life to God in unity with the sacrifice of Christ for the salvation of the whole world. For this reason, the Synod of Bishops asked that the faithful be helped to make their interior dispositions correspond to their gestures and words. Otherwise, however carefully planned and executed our liturgies may be, they would risk falling into a certain ritualism. Hence the need to provide an education in Eucharist faith capable of enabling the faithful to live personally what they celebrate.... (§64)

Pope Benedict XVI stressed the need for formation and instruction about the Sacred Mysteries of the Eucharist (“mystagogical catechesis”), so that Catholic people will more fully understand and be able to unite themselves interiorly with the action of the Eucharist. The Holy Father specifically mentions signs and gestures.

Part of this instruction about the mystery of the Eucharist, the pope writes, involves the meaning of ritual gestures: A mystagogical catechesis must also be concerned with presenting the meaning of the signs contained in the rites. This is particularly important in a highly technological age like our own, which risks losing the ability to appreciate signs and symbols. More than simply conveying information, a mystagogical catechesis should be capable of making the faithful more sensitive to the language of signs and gestures which, together with the word, make up the rite. (§64, b. Original emphasis.)

The origin of most of these symbolic gestures that are integral to Catholic worship — a wordless liturgical language — is, in many cases, lost in history. A basic vocabulary would include genuflecting toward the altar and tabernacle, bowing the head at the name of Jesus and when the names of the Trinity are pronounced (the Doxology, or “Glory be…”), along with bowing toward the crucifix, striking the breast and making the sign of the cross. They do have meaning and significance as powerful signs of worship even if the way this happens is only dimly understood.

The vocabulary of ritual gestures Catholics make during worship is by now, quite clearly, endangered — as has happened with other unwritten languages. As there are relatively few explicit rules (and even these are often not followed), little uniformity of practice, and considerable confusion, it seems worthwhile to compile a sort of “dictionary” of ritual gestures, their meaning and grammar, in order to relearn our historic language of ritual worship.

1. Signs and Gestures During Mass - Entrance Rites:

Some examples are listed below.

- Make the sign of the cross with holy water (a sign of baptism) upon entering the church.

- Genuflect toward the tabernacle containing the Blessed Sacrament and the Altar of Sacrifice before entering the pew. (If there is no tabernacle in the sanctuary, or it is not visible, bow deeply, from the waist, toward the altar before entering the pew.)

- Kneel upon entering the pew for private prayer before Mass begins.

- Bow when the crucifix, a visible symbol of Christ’s sacrifice, passes you in the procession. (If there is a bishop, bow when he passes, as a sign of recognition that he represents the authority of the Church and of Christ as shepherd of the flock.)

- Make the sign of the cross with the priest at the beginning of Mass.

- Bow and make the sign of the cross when the priest says “May Almighty God have mercy…”

- Bow your head when you say “Lord, have mercy” during the Kyrie.

- If there is a Rite of Sprinkling (Asperges), make the sign of the cross when the priest sprinkles water from the aspergillum in your direction.

- Throughout the Mass, bow your head at every mention of the name of Jesus and every time the Doxology [“Glory be”] is spoken or sung. Also when asking the Lord to receive our prayer.

- Gloria: bow your head at the name of Jesus. (“Lord Jesus Christ, only begotten Son…”, “You alone are the Most High, Jesus Christ…” )

2. Signs and Gestures During Mass - Liturgy of the Word:

Some examples are listed below.

- When the priest announces the Gospel, trace a cross with the thumb on head, lips and heart. This gesture is a form of prayer for the presence of the Word of God in one’s mind, upon one’s lips, and in one’s heart.

- Creed: Stand; bow your head at name of Jesus; on most Sundays bow during the Incarnatus (“by the power of the Holy Spirit … and was made man”); on the solemnities of Christmas and the Annunciation all genuflect at this moment.

- Make the sign of the Cross at the conclusion of the Creed at the words “I believe in the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come. Amen.”

3. Signs and Gestures During Mass - Liturgy of the Eucharist:

Some examples are listed below.

- If incense is used, the congregation bows toward the thurifer when he bows to the congregation both before and after he has incensed them.

- The congregation remains standing until the end of the Sanctus (“Holy, holy”), when they kneel for the entire Eucharistic Prayer.

- At the moment of the Consecration of each element, bow the head and say silently “My Lord and my God”, acknowledging the Presence of Christ on the altar. These are the words of Saint Thomas when he realized that it was truly Christ who stood before him (John 20:28). Jesus responded, “Because you have seen me, you believed. Blessed are they that do not see and yet have believed” (John 20:29).

- Reverently fold your hands and bow your head as you pray the Lord’s Prayer. (Special note should also be made concerning the gesture for the Our Father. Only the priest is given the instruction to “extend” his hands. Neither the deacon nor the lay faithful are instructed to do this. No gesture is prescribed for the lay faithful in the Roman Missal; nor the General Instruction of the Roman Missal, therefore the extending or holding of hands by the faithful should not be performed).

- Kneel at the end of the Agnus Dei (“Lamb of God…”).

- Bow your head and strike your breast as you say, Domine non sum dignus... (Lord, I am not worthy...)

4. Signs and Gestures During Mass - Reception of Holy Communion:

Some examples are listed below.

- Make a deep gesture of reverence (bow) as you approach the priest in procession to receive Holy Communion. If you are kneeling at the Communion rail, no additional gesture is made before receiving.

- If you also receive from the chalice, make the same gesture of reverence when you approach the minister to receive.

- Make the sign of the cross after you have received Holy Communion.

- Kneel in prayer when you return to your pew after Holy Communion, until the priest sits down, or until he says “Let us pray”. (GIRM 160 American adaptation says that people may “stand, sit or kneel”.)

5. Signs and Gestures During Mass - Conclusion of Mass:

Some examples are listed below.

- Make the sign of the cross at the final blessing, as the priest invokes the Trinity.

- Remain standing until all ministers have processed out. (If there is a recessional, bow in reverence to the crucifix as it passes by.)

- Genuflect reverently toward the Blessed Sacrament and the Altar of Sacrifice as you leave the pew, and leave the nave (main body) of the church in silence.

- Make the sign of the cross with holy water as you leave the church, a reminder of our baptismal obligation to carry Christ’s Gospel into the world.

You can do it, too! Sign up for free now at https://www.jimdo.com